Will you be see the collapse in the property market coming?

Will you be see the collapse in the property market coming? There is an entire industry of vested interests out there to ensure that you don’t. You have a Government whose declared purpose is to juice demand and support funding with its various schemes to encourage the consumer to put themselves further into hock at current inflated levels. You have the entire financial services industry also pushing the same story along with its cheerleader, the central banks. We are confidently told that the economy is now recovering and as an apparent confirmation of this, Rightmove has reported a month on month increase in central London asking prices for properties of over 10%!

As with any good magic trick however, the audience needs to be distracted from the real slight of hand.  Behind the headlines of meaningless asking price expectations, a number of long-standing property investors, both UK blue chip as well as overseas (including Russian and Saudi) have been quietly divesting some of their trophy property assets. Rental prices meanwhile are also beginning to crack (check out Zoopla), initially in the financial services exposed areas such as Canary Wharf, but now more recently in Westminster. While asking prices to sell properties may be up over 10% on September, year-on-year rental prices are in places falling by over double this level as increased capacity meets falling demand (and ability to pay). The Government may be trying to buy votes at the lower end of the ladder with its help to buy scheme, but remember that the additional servicing costs will be passed on to borrowers while banks increasingly curtail interest only mortgages. In some markets such as Canary Wharf, where up to 80% of apartments are buy to let, things look scary. By way of example, nine months ago a large three bedroom flat at the better end and with a good river view would cost you around £1,250 pw (£65,000 pa) to rent and perhaps £1.15m to buy, representing  a gross yield of approx 5.5%, albeit nearer 4.8% after the steep service costs of over £10k pa. About five months ago however, rentals on comparable properties were down to £970 pw and are now on offer at £800pw; a drop of over a third in a year. Asking prices meanwhile have yet to reflect this trend, but the maths is not good. On said above property, even assuming an average entry price for your buy to let merchant of £1m, the gross yield at £800 pw would be a net yield of barely over 3%, even assuming a rental over a full 12 month period. At these levels the properties would start to become cash-flow negative even on an interest only funding basis. While big players may have the cash resources to swallow this for a time, smaller ones would be under pressure to sell. This dynamic in itself could well start a stampede for the exit, even without a possible rise in rates.

UK property – a narrowly based bubble

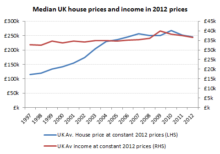

QE funds government deficits, but the accompanying financial repression and hot money only serves to leverage up asset prices rather than the economy’s real ability to service them once rates normalise. In 15 years, UK average house prices have more than doubled after inflation, while average real incomes are only up 12%.  As a consequence average property prices relative to average incomes have more than doubled over the period, from around 3.5x to almost 7x overall for the UK and to almost 9x income for London.

With no real income growth and rising food and energy demands on household budgets this relative rise in UK property values has been funded by credit initially, and now more recently with lower mortgage rates. In essence, the doubling of property values is now supported by a halving of mortgage funding costs.  If one were to apply the UK standard variable mortgage rate to average property values for England and London, then the dangerous excesses up to 2008 (equity withdrawal fuelled) can be clearly seen with imputed(*1) property costs rising to over 50% of income in England and 60% in London. As credit tightened, rates had to be slashed to avoid a very sharp contraction in consumption. However, reducing the consumers’ property burden with a temporary fix on mortgage rates rather than an increase in income merely defers the problem. The Government is clearly desperate to avoid the reckoning, but with government deficits persisting, they will eventually lose control of long term rates. Should this precede a recovery in incomes, as it assuredly will, then property values will need to contract if there is limited further give elsewhere in household budgets and scope to equity release.

The Government needs low rates, the Governor of the Bank of England would like to oblige, but ultimately their ability to control rates is limited so long as they need to fund deficits without crushing consumption with further taxation. While every other Govt/Central bank in town has been playing the same QE game, competition for capital has been neutered and so with it have rates. There may be an assumption that the UK is the master of its interest rate destiny, although a quick look at the comparative mortgage rates in the UK and US suggests the futility of this.

(*1) Yes, not all homes are funded with a 100% interest only mortgage at prevailing property values, but this imputed figure also provides an opportunity cost to the equity component and therefore a valid measure of property service cost relative to average income.