Mediaset is still looking like a value trap

Reviewing last week’s Mediaset results I was struck by a sense of deja vue. Here was a company that for a third consecutive year was denying that it was not trying to sell its lossmaking PayTV unit (Mediaset Premium) in the face of supposedly well sourced rumour to the contrary, this time to Vincent Bollore’s Vivendi. For those that care, Mediaset Premium is an ITV Digital look-a-like, where a leading commercial TV broadcaster has tried to take on a Sky incumbent by buying up lots of expensive football TV rights. In 2002, ITV Digital went into administration. In 2015, Mediaset Premium made undisclosed losses after the first year of its €700m three year Champions League rights contract.

For such a pivotal strategic investment, the group is remarkably coy as to the financial numbers. We have the year-end subscriber number, which edged up to just over 2m again (2.010m), albeit slipping back in Q1 FY16 after the €4 per month price increase, but little else. Looking at the transcript of the post results conference call (http://finance.yahoo.com/news/edited-transcript-ms-mi-earnings-193329684.html), one analyst at least finally asked the obvious question “And for the fourth question is can you tell us anything about the profitability of pay in 2015 whether it made money or lost money or better give us the EBIT?” The fourth question and asking whether it was profitable! I assume the question was part rhetorical as excluding El Towers (€73m of EBIT), Mediaset’s overall Italian operations were heavily lossmaking, to the tune of around -€47m at the EBIT level. This, on an activity that generated over €1.7bn of net advertising revenues (NAR), an almost 58% market share. Notwithstanding a few tough years, Mediaset ought to be making EBIT margins of at least 20-25% on what is a dominant commercial broadcaster of some scale. What that means is a core commercial TV EBIT in a range of €342-428m and therefore a PayTV loss for Mediaset Premium of €389-475m. Was it profitable, my a@#e!

It does however explain why:

- Why they don’t want to talk numbers to those who ought to be demanding them, preferring instead to refer obliquely to “the first season would have been a lossmaking season. The next season will be almost breakeven and clearly the last season we’ll recapture what has been lost in the first season”. I wasn’t sure whether this was the CFO speaking or Chancey Gardiner. What was clear was that it was anything but.

- Why they might be eager to exit what is looking like an ITV Digital re-run by sucking Vivendi into a strategic venture along with Telecom Italia, where it has a 23% stake.

- Why the rumours include suggestions that Vivendi is resisting the price that Mediaset is seeking for Mediaset Premium.

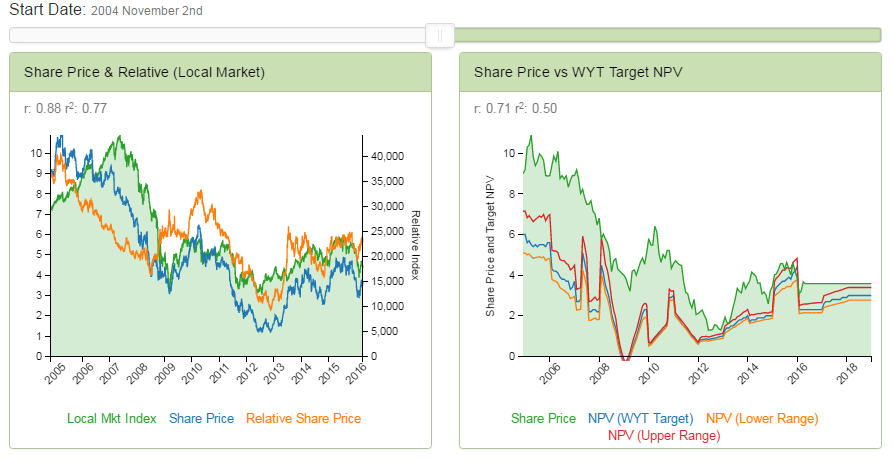

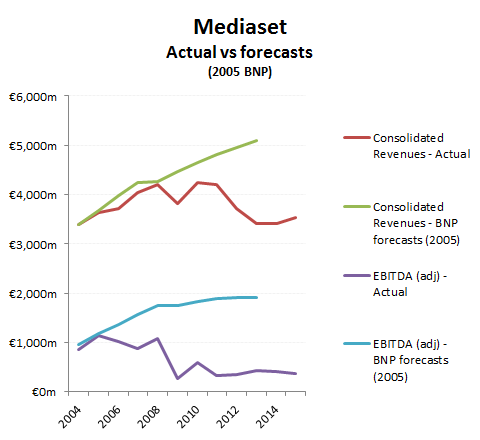

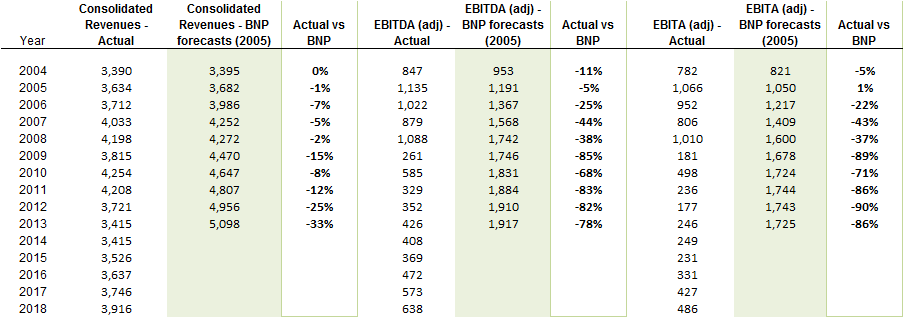

While reviewing this topic I stumbled on an old analyst report from BNP in January 2005

While in no way wishing to disparage the unfortunate author, I merely wish to use it as an example of big bank research and why markets rarely reach out beyond about 18 months to discount growth from a company. If you read it you will also note that there is barely a cursory glance towards a valuation analysis, merely a reference to an undisclosed SOTP (sum of the parts) valuation that must have been kept back in the office. As with all sell side research, it is intended to stimulate a Buy or Sell decision (ie income for the bank) and therefore is centred around an equity ‘story’; in this case the great opportunity for Mediaset in pay TV and the upward only revenue and EBITDA progression which accompanied the valuation upgrade from €10.0 ps to €11.4 ps (vs less than €4 ps now).

Great payTV opportunity .. Really?

While the example of ITV Digital must have been fresh in anyone’s mind, for Mediaset, this time clearly it was expected to be different. Well it hasn’t been and with shortfall in revenues and earnings, so the shares have declined, notwithstanding the strong performance of its Spanish consolidated subsidiary Mediaset Espana.

This is why markets keep valuation horizons close

Compare the forecasts with the actual

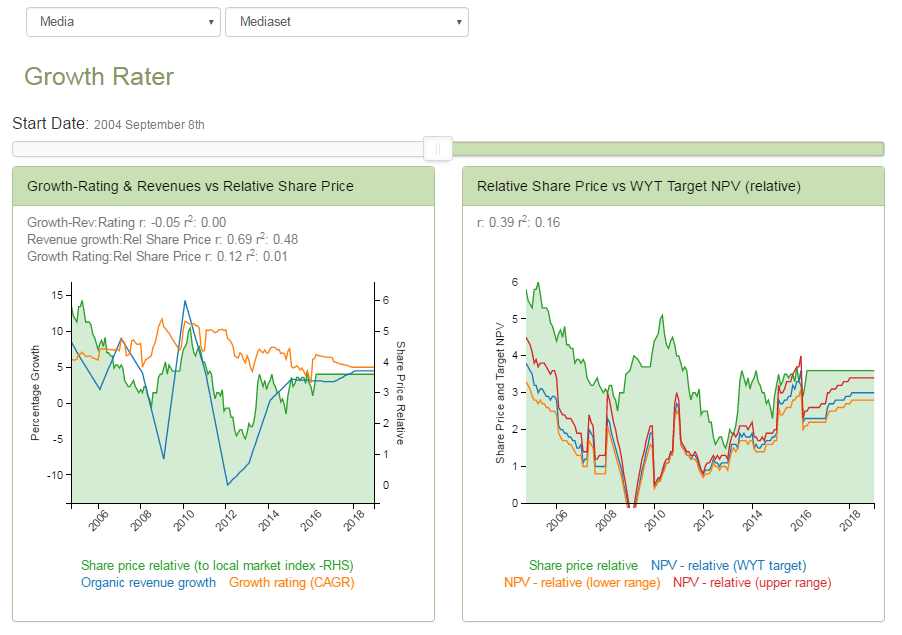

This is why markets will only reach out beyond 18 months if a group is generating super-normal organic revenue growth and why we also recognise that in our valuations. It also highlights the need for a transparent and structured approach to valuation. Again there are no black boxes in the GrowthRater. You can measure growth delivered against the growth being priced into an equity and also manipulate the core revenue and margin assumptions to recalibrate the valuations as well measure valuation volatility/risk. You might think there’s a good equity story, but how do you know if it’s already been discounted by the price. Wait for a big sell side to show you its SOTP?

Check out the GrowthRating