Treasury yields after debt ceiling ‘can-kicking’

Kabuki theatre remains alive and well in DC, and yet again, after all the histrionics from both sides of the aisle, the government will just keep spending money it doesn’t earn. While details have yet to be released, it seems the best result that Speaker McCarthy could secure was a budget cut of a measly $50bn, in return for expanding the debt ceiling by $4 trillion for the next two years (2025 and after the next presidential election). Disappointed perhaps that yet another opportunity to control runaway spending has sunk without trace again in the DC swamp, but no one should be particularly surprised. They have to fund their war and nothing was going to stand in the way of a group prepared to “burn his own nation to the ground to rule over the ashes.” – sun-tzu

What we know so far of the ‘deal’

As of writing (am Sunday 28th May), there’s nothing up on the House Speaker’s (Kevin McCarthy) website on this supposed provisional agreement on the US Govt debt ceiling, while the latest release by the White House merely states that a “budget agreement in principle” has been reached. According to Reuters, this ‘tentative’ agreement runs to January 2025 and includes the already budgeted +11% increase in defense spending to $885bn, albeit the +$85bn of additional funding won’t last long at the rate Ukraine is burning through munitions, including those ammunition depots that the Russians keep blowing up.

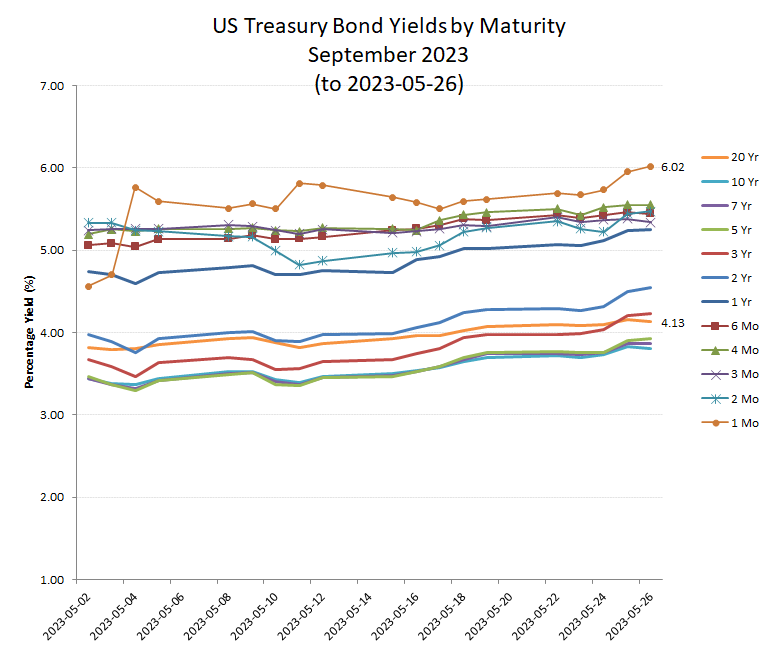

But what of T-Bill yields?

Where we are: The last couple of months has seen some pretty extraordinary gyrations in yields, particularly at the short end, which included the collapse in the 1 month yield in April (Euro-dollar collateral shortage) and subsequent recovery with a rising trend of yields across all maturities. The key feature here though was the heavy premium in terms of yields at the shorter end, where the 1 month yield is now +189bps ahead of the 20 year yield. At the same time, US dollar short term deposit rates at banks and financial institutions had started to diverge from the comparable maturity T-Bill yields. So while short dated (<1Yr) T-Bill yields have increased by almost +100bps to around 5.4%, rates for similar maturity fixed term deposits have in places dropped over -150bps to nearer 2.5%.

The only explanation I find that fits these events is the risk of default (or delays) on T-Bill interest payments which would have been used by fixed deposit takers to cover their own interest commitments to depositors. Hence the expansion in their margin in order to compensate for this additional risk. While rates have been rising across the whole maturity curve, the lower yields at the longer end reflect the expectation of falling rates of inflation and therefore compensatory returns for bond holders. While temporary debt ceiling disruptions to interest payments might also impact this group, this would both be proportionally less than at the short end and also compensated by a greater confidence in the administration’s commitment to tackle excessive expenditure and therefore inflation.

So what now?

While this might be excused as another politically expedient decision for all parties to muddle their way to the next election and so abrogate responsibility to voters, it also represents anther attempt to ‘kick of the can down the road’. As such, there is nothing here to support confidence that there is the political will in DC, or amongst the electorate to avert the inevitable, that of a currency crisis. When that happens, remains uncertain and will in part depend on the pace of de-dollarisation which is already taking place from the BRICS to the rest of LatAm and Africa. As a transaction medium, this may take time (most empires decay slowly from the head, before the body dies), but as a store of value, investors will need to look elsewhere, or at least demand compensatory rates of return.

The net conclusion of all of this, is that yields at the short end may initially fall to reflect the lower risk of immediate default/delay on interest payments, but those at the long end should rise to reflect the inflationary risk from the lack of resolve to tackle the root cause of inflation and on a purely mechanical basis, to reflect the additional debt that the US treasury will be trying to sell to investors. Rising supply into falling demand, usually has one outcome!