Equity’s siren call into early stagflation

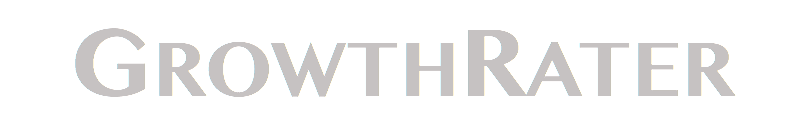

Has the US Federal Reserve lost control of the narrative? Much as it has tried to sound hawkish, its actual actions into the first half of this year have instead communicated a lack of real resolve, which along with the political retreat on fiscal control with the abandonment of the ‘debt ceiling’, has left equity markets following the line of least resistance and liquidity. The Q1 easing and subsequent explosion in deficit and federal debt in Q2 however, are not sustainable, if the US dollar is to be defended. For H2, a resumption of the planned balance sheet reduction by the Fed in face of a increased deficit spending will expand the already rising requirement to sell its debt, further exacerbating the competition for funds and therefore interest rates. Those hoping for a return to monetary easing driving further liquidity into equity assets, as the below chart on central bank assets and the S&P500 suggests, may therefore get rudely disabused of this by the second phase of the stagflation cycle. That is when the reverse happens, when liquidity is drained from the productive private sector to fund the unproductive black hole of the public sector.

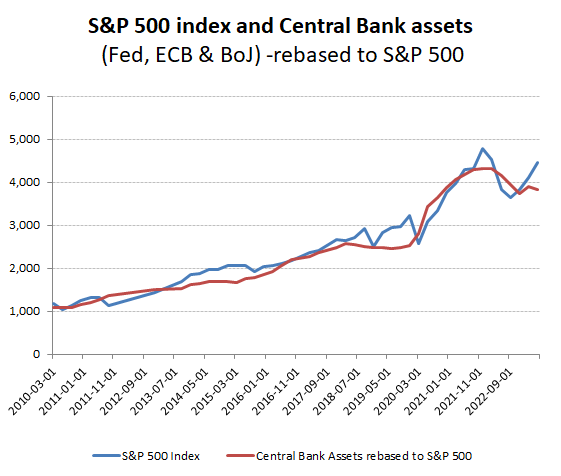

Equity yields have been falling as prices recovered in H1, but the message from the bond markets have suggested the opposite and particularly more recently as yield increases extend up the maturities. While equities rise on the hope of a resumption of fiscal and monetary easing, bond markets are increasingly coming to terms with the prospects of a much more protracted period of tightening and higher interest rates.

Much spurious guff is written about the relationship between interest rates and inflation. Listen to the politicians and we are told that we have to suffer higher interest rates because we need to be poorer to make us more reluctant to spend on goods, which would otherwise help to drive up their prices. Of course in this narrative, inflation has nothing to do with the excess growth in the money supply, often to monetise spending deficits on areas generating below market returns (ie value destructive) by those same politicians. Grow money (or credit) faster than production and the first will decline in value relative to the latter. Little has changed in two thousand years when Suetonius (on Octavius (Augustus) in The Lives of the Twelve Caesars) wrote

“by bringing the royal treasures to Rome in his Alexandrian triumph he made ready money so abundant, that the rate of interest fell, and the value of real estate rose greatly.”

Suetonius may have equally referred to the price of money declining “greatly”. Octavius however, was doling out actual cash (gold), rather than the IOU’s that our politicians spend. Unlike for Octavius, expenditure above income by current governments mean their budgets are in deficit and once they can no longer monetise those with fiat creation (such as with QE or concocting a war and stealing their gold), they are therefore short of cash and need to borrow, thereby resulting in the reverse scenario

“by spending all the royal treasures and credit in their endless wars they made ready money so scarce, that the rate of interest rose, and the value of real estate fell greatly.”

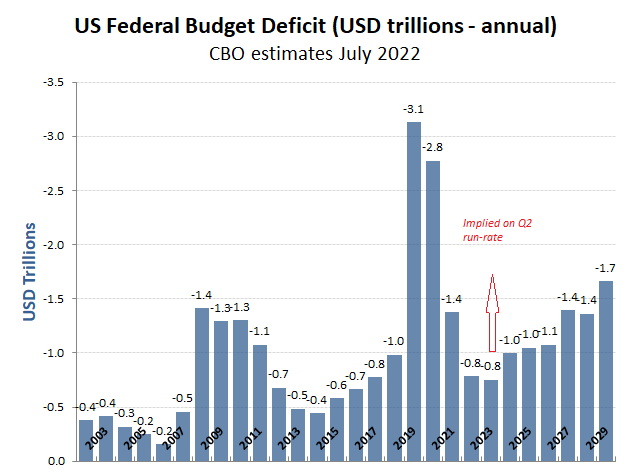

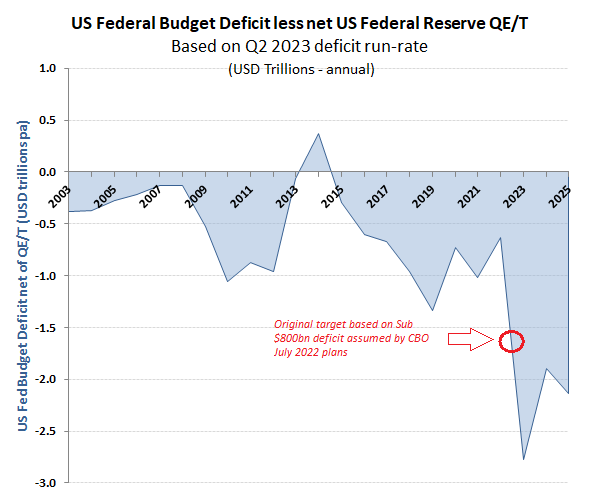

For the US, the $862bn increase in Federal debt in Q2 (+$1.7tn YoY) to approx. $32.32 trillion, following the suspension (again) of the so-called ‘debt ceiling’ represents a further deterioration on an already tenuous financial situation, while suggesting a possible significantly higher effective deficit than the approx $800bn projected for 2023 this month last year by the CBO.

Higher deficits mean the US government will need to find more buyers of it’s debt to fund it, while inflation will force it to also adhere to its planned unwind of its >$4tn of previously monetised deficits still sitting on its own balance sheet. In Q2, that balance sheet unwind amounted to approx $365bn, which implied a run rate of ~$122bn per month, with the excess over the planned $95bn pm probably reflecting some catchup after the Q1 easing (post SVB, First Republic and Signature bank bailouts). That however, still leaves the Fed needing to find buyers for around $1.1tn pa of its own bond holdings and what is now looking like a further $1.5tn pa of the government’s own debt issuance. So while the US is looking to sell upwards towards $3tn of new debt, the ECB, BoE, BoE are in similar positions and deficit pressures and moves at de-dollarisation elsewhere suggest a further possible US bond overhang.

Money is a commodity and its price is measured by the (interest) return one has to offer the market to buy or sell it. If the economy and opportunities to generate high ROIC emerge, then demand will increase for that money as will the price and rate of interest one might be able to afford to acquire that money for onward investment. Government deficits and demand for money however, can often crowd out the commercial market and particularly when an ideologue agenda delays the inevitable restoration of fiscal reality. This is when markets need some patience to look thru the political cycle, where often the pain and absurdity of the existing failed policies may take time to deliver those reforms, as so evident in both the UK and US in the 1980’s after the chaos of the 1970’s.

We are therefore entering a protracted period of monetary tightening that has yet barely touched the consumer. As previous fixed rate mortgage/loans roll into high rate ones and as funding costs continue to rise as governments keep doubling down on deficit spending on low/zero return projects to buy votes, these will progressively impact discretionary disposable incomes. For equities, which into the initial stages of stagflation appear fairly resilient, that will erode pricing power and top line growth, while reducing opportunity value on M&A as marginal ROIC is squeezed from both ends. At some point the political narrative will have to recognise that expensive energy, food, social policies are detrimental to growth as are tax disincentives and the reckless fiscal and foreign policies currently being pursed. For the investor then, that becomes a political assessment of whether we are ready for another Thatcher/Reagan, or still mired in the World of Callaghan and Carter.

Some hopefully helpful context

- Philip Lane chief economist ECB: Rates higher and for longer as central banks face secondary inflation wave

- Last FOMC meeting: June 13-14 (Minutes released July 05)

“The vast majority of respondents to the Open Market Desk’s Surveys of Primary Dealers and Market Participants expected no rate change at this meeting.

Respondents’ average probability distribution for the level of the peak policy rate shifted higher since the May meeting and respondents on average assigned about 60 percent probability to the peak being above the current target range. The market-implied path for the policy rate continued to show some decline this year but less so than it had in recent months.

Desk survey respondents still saw a recession occurring in the near term as quite likely, but the expected timing was again pushed later, as economic data pointed to the continued resilience of economic activity. Overall, respondents generally continued to expect that any downturn would be neither deep nor prolonged. With regard to inflation expectations, respondents marked up their projections for quarterly core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) inflation in the second and third quarters of this year, while projections for later quarters were little changed.

“almost all participants judged it appropriate or acceptable to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5 to 5¼ percent at this meeting.”

“All participants agreed that it was appropriate to continue the process of reducing the Federal Reserve’s securities holdings, as described in its previously announced Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet.”

“maintaining a restrictive stance for monetary policy would be appropriate to achieve the Committee’s objectives. Almost all participants noted that in their economic projections that they judged that additional increases in the target federal funds rate during 2023 would be appropriate.

A few participants noted that there could be some upward pressure on money market rates in the near term as the Treasury issued more bills to meet expenditures and return the balance in the TGA to the Treasury’s preferred level.

“The members agreed to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 5 to 5¼ percent. Members agreed that holding the target range steady at this meeting allowed the Committee to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy. In determining the extent of additional policy firming that may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, members concurred that they will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments. In addition, members agreed that the Committee will continue to reduce the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities and agency debt and agency mortgage-backed securities, as described in its previously announced plans. All members affirmed that they are strongly committed to returning inflation to their 2 percent objective.”