Yellen does virtuous – 5 years too late!

Confused? Well you should be be if you’ve been believing the usual output from the Federal Reserve. Contrary to the narrative of robust US economic growth and tightening labour markets requiring a normalisation of interest rates, things aren’t quite as rosy as Ms Yellen had been suggesting. Behind the increasingly absurd non-farm payroll data with its manipulated seasonal adjustments and over-egged GDP forecasts by the Atlanta Fed, the Fed appears to have been trying to dial back the growth story, and with it the prospective rate tightening.

While Ms Yellen at her semiannual address to congress was holding the official line of steady growth in GDP/jobs supporting the progressive programme of interest rate rises and Fed balance sheet reductions, colleagues such as governor Lael Brainard are painting a more dovish picture, saying that “the neutral level of the federal funds rate is likely to remain close to zero in real terms over the medium term” and that “if that is the case, we would not have much more additional work to do on moving to a neutral stance”.

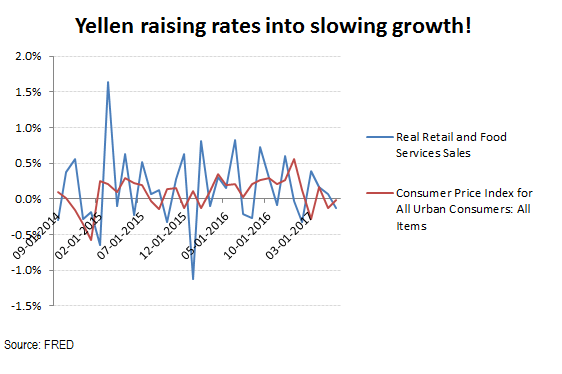

Translated, this presumably means that we’re not too far off normalised rates already (ie party on dude!). Given the subsequent figures that came out on Friday for June retail sales growth (of -0.2% vs the street at +0.1%) and CPI (of zero vs the street at +0.2%) and the lethargic improvements in private sector wages and real job growth, this however, shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. The reaction from the markets meanwhile to expectations of slower GDP growth and a softening of the monetary tightening meme, were also fairly predictable; the US dollar eased back while equity prices reacted positively.

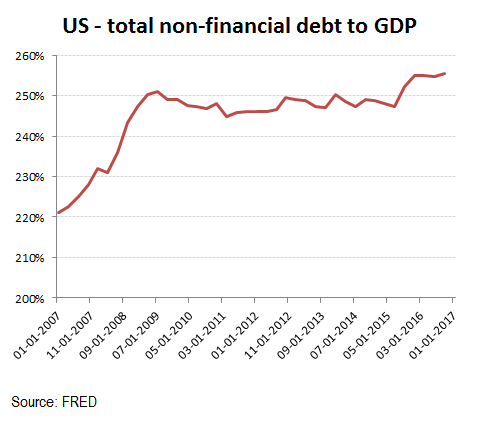

Like the Oracle in the Matrix film, Central banks manipulate behaviour by saying what they think markets need to hear rather than the truth. When Yellen moved monetary policy on to a hardening cycle, it had less to do with responding to improving economic newsflow and inflation expectations and more to discourage further consumer credit growth without actually pulling the plug on the economy with a substantive real increase. Like Gordon Brown in the UK, Barrack Obama’s legacy has been to saddle both the public and private purse with yet more debt. With an effective budget deficit of still over $1bn in his last year in office, Federal debt is approaching $20bn (and over 100% of GDP), which if included with all the non-financial corporate and private debt must be approaching $50bn and a almost 260% of GDP. Once the debt overhang and prospect of rising funding costs starts to depress consumption, the ability to outgrow this tidal flow of increasing obligations also recedes. Someone always has to pay, the question is just who and when. If not the borrowers from future consumption, then these obligations fall back on the lenders, which includes of course currency owners.

Clearly the Keynesian multiplier effect hasn’t worked in stimulating growth on the way up, but at issue will be whether it applies on the way down. Since the the start of 2010, US GDP has increased by just $4.3bn against a rise in Federal debt of $7.2bn (including a +$2.23bn increase to $4.5bn ‘monetised directly onto its own balance sheet) while total US non-financial debt has increased by $11.6bn. If the US is running a Federal deficit of approx $1tn pa even when rates are under 0.5% and GDP growth is >+2% pa, just imagine the impact of even adding +100bps to funding costs on a near 3:1 debt:GDP ratio, low household savings ratios and elevated sub-prime auto delinquencies. Having presided, with Bernanke over an irresponsible balance sheet expansion under Obama, it does seem like breath-taking Chutzpah for Yellen now to be preaching fiscal honesty to Congress

“Let me state in the strongest possible terms that I agree” the U.S. federal debt trend is unsustainable, may hurt productivity, and living standards of Americans.

Monetary tapering now probably too little too late!

So how does this play out? Markets will squeal at lower GDP growth and the prospects of tighter monetary policy and will again demand the punch bowl back. We’ve seen it many times before and the more dovish comments by Fed governors such a Brainard suggest they know their practical scope to harden rates is limited and they will again try to take the line of least resistance and keep the monetary taps flowing. Politically however this policy is becoming increasingly untenable. This last decade of QE has topped a generation of excess spending where the costs have been deferred to future generations. The new generation who are coming out of college with record debts and dismal career prospects and nowhere affordable to live have every right to be angry at the greed and mismanagement of their elders. Trump and Brexit are manifestations of this, as is Macron. Assuming one can just continue to follow the past investment strategy of BTFD, may therefore no longer be valid.

Short term, a more dovish narrative from the Fed in response to easing GDP growth expectations will take some of the pressure off US equities, although the continued discussion about reversing some of its bond holdings if not offset by looser credit availability may curtail market liquidity. This however still leaves the structural issues of the deficit and internal investment unresolved by the “lawmakers”. Unfortunately the sclerotic Congress has been unwilling to meet its fiscal responsibilities while the Fed was happy to monetise the deficits, which has also been the experience in Europe. What may be needed is either a crisis, such as a heavy contraction in Q3 GDP expectations, and/or a resolution of the Russian ‘hacking’ allegations that have mired the new President’s tax and healthcare reform proposals. If Trump can gain a clean bill of health once the Muller inquiry reports by the autumn, then this ought to help restore his credibility with at least his own party in Congress which in turn may offer the best hope of securing the fiscal reforms needed to control outgoings and stimulate internal investment and avoid entering into a debt spiral.

In summary, a dovish Fed provides a short term relief to equity markets, but may have limited follow through. Indeed, economic growth expectations may need to take a hit first and Trump still needs validation from the ‘Russian hacking’ investigation before one might wish to push for higher valuations, but perhaps after a lean summer.