How ‘free’ is your ‘free cash flow’?

Back in January, Alphabet decided to take the high ground in its reporting by including Stock Based Compensation (SBC) within its adjusted ‘non-Gaap’ earnings’. As a bit of an old chestnut for analysts and portfolio managers and something the IASB has mandated to be included in IFRS reporting since 2005, it was perhaps no surprise that the confirmation from Alphabet CFO Ruth Porat that it does indeed represent a true expense had little impact on the shares.

“Although it’s not a cash expense, we consider it to be a real cost of running our business because SBC is critical to our ability to attract and retain the best talent in the world.”

The assertion that SBC is “not a cash expense” however, depends on your perspective and can highlight a more fundamental divergence in priorities between management and shareholders. Shareholders may own the equity, but management may answer to a broader group of ‘stakeholders’ in the business; something that is often overtly expressed in many Continental European articles of association and supervisory boards. That means that management may look at equity as just another cost of capital to be used and serviced whereas the shareholders and ultimate owners of all the assets and liabilities will have a very different perspective.

For a management, paying staff compensation in equity may seem like a ‘non-cash’ cost, but from the perspective of the existing shareholders, the dilution represents a real transfer of value from them to those providing a service to the company. It also reflects a real cash cost to shareholders, which is often obscured by the form of the award and exercise period. When the transfer has an intrinsic value, the value is self-evident, although even here is often missed. Pay your CEO $100m in cash and it clearly is both an expense and cash item in your cash flow, regardless whether the cash came from earnings, debt or SHARE ISSUANCE. Paying the CEO the shares directly for them to sell does not change the nature of the transaction nor value transfer, albeit it may be excluded from an adjusted earnings line, while the cash flow element will be included amongst the share issues and share buybacks, thereby inflating the apparent ‘free cash flow’. Moving from an ‘intrinsic’ to a ‘fair value’ basis of valuing the SBC, is merely just a more efficient way of recognising the current value that is being transferred, but one which still reflects the future potential cash cost or lost opportunity value. There may be better ways of determining the ‘fair value’ than a Black-Scholes model and volatility assumption designed for tradable options, but that shouldn’t alter the validity of trying to impute a charge that reflects a real transfer of value.

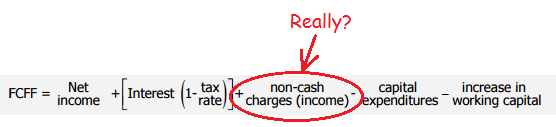

This gets me back to the issue of “how free is your free cash flow”. Intuitively, the concept seems simple, but as shown by the treatment of SBC, can vary depending on one’s perspective. For a management, dividends may represent a cost of funding the business (and therefore not free), but SBC are a non-cash cost and can be excluded. From the shareholders perspective however, the excess cash flow from the underlying business is all owned by them, regardless of whether they decide to allocate it to dividends, acquisitions or whatever else takes their fancy. Unfortunately these two divergent perspectives are conflated in definitions of ‘free cash flow’ such as in the one below for unleveraged free cash flow (FCFF). From the perspective of management, one might want to include dividend funding costs, while from a shareholder perspective, inflating operating free cash flow for the cost to yourself from SBC dilution is clearly perverse.

The key take-away from all this, is that if you are valuing the shares, look at the ‘free cash flow’ from the perspective of the shareholders and be careful of taking definitions and figures from management who may be at cross purposes with you. It also means that even if you are working up from changes in net debt to get to an implied free cash flow figure by excluding non-operating items such as dividends, net acquisitions and share issuance, this later line item may also contain SBC. With companies engaging in heavy share buy-back programmes, identifying the hidden component that represents SBC can therefore be difficult, albeit the net P&L charge is probably a good place to gauge the underlying contributions to reported free cash flows and therefore the extent one should aim off from these figures to determine normalised levels of free cash flow and operating free cash flows. What you may find are many groups with a somewhat less impressive rate of net income to free cash flow generation that had previously been believed from simply cranking out conclusions from the reported figures. This is why analysts need to ‘clean up’ the reported data and investors need to be discerning of the quality of data (such as ‘free cash flow’) on which their investment decisions may depend. As the old adage says, “Rubbish in, rubbish out!”

The elephant in the room meanwhile remains the extent to which ‘non-cash charges’ such as acquired intangible amortisation may represent a consumed asset, as the arbitrary nature by which these are amortised usually means these are ignored for free cash flow and valuation purposes. This however is a rabbit hole that markets are reluctant to go down and is something for a further blog.