Recency bias – the curse of financial markets!

We are all guilty of it, but it is probably the single most dangerous investment sin. Perhaps it is part of our social evolution to conform. A sort of “Eat shit 17 quadrillion flies can’t be wrongâ€. With regards to financial markets you may have seen the same shit, but given a pseudo- intellectual spin such as “perfect market theory†or its ilk which implicitly suggest that markets are right and you are wrong, albeit an imperfect market theory would be just as valid. Human capacity for self-delusion based on information and normative conformity bias is well documented and includes Asch’s classic Conformity experiment which is well worth watching, if only for the appalling 1970’s hairstyles.

//www.youtube.com/watch?v=sno1TpCLj6A

Ok, so over the past five years we have been taught that bad news is good news as market liquidity is dominated by central bank policy and that all dips should be bought (see //www.youtube.com/watch?v=0akBdQa55b4) and that yield is good, almost regardless of risk. If it’s gone up in price, find a justification, however spurious and then flex the assumptions to add at least 10% to the price to keep compliance happy with the endless buy recommendation. This self-reinforcing consensus however is little more than a mass goal-seek. Sell side careers do better during the longer periods of cyclical upswing and if it all goes pear-shaped, then the flawed recommendation can be buried along with the general debris. For buyside, the pressure on short term returns is also intense and bucking the trend can also be expensive to careers, ergo momentum investing rules and in turn merely reinforces the conformity bias until the big reset. A particularly interesting feature of the Asch experiment was also the effect of introducing an additional potential dissenting voice to the group and the speed at which it could puncture the group delusion. Quite what will represent that ‘additional voice’ in today’s markets will have to be seen, but take care because when it happens, as it always does, it will be quick.

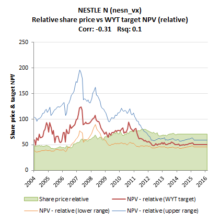

I was reminded of the pervading power of recency bias in a meeting with an investment manager who was interested that my growthrater system did not share his upbeat view of the value of a stock; in this case Nestle, a solid consumer group with a good record of historic growth but with current revenue growth falling short of the expectations that rising Asian demand were expected to deliver. Notwithstanding, the investor was probably referring a post interest cost of capital (WACC) rather than a more robust pre-interest one, his position was that the market (aka big sell-side) were pushing the stock on the basis of a seriously sub-market cost of capital. If growth is slowing and volatility increasing however, this looked more like a goal seek to justify where the stock, or they would like it be, rather than a serious revaluation argument. In the ‘growth-rater’, the equity risk premiums used are those for the market average, with the flex in target operating free cash flow yield determined by variances in discount growth rating. Unlike the above flexing of specific risk premium, this is not a function of a subjective discount plucked out of the air to goal-seek a share price, but directly related to what the company is actually achieving and is expected to deliver in terms of organic revenue growth. As a consequence it is considerably more immune from the group goal-seek. It may provide uncomfortable results, but this should be expected from any rigorous structured approach. My response to the cost of capital issue on Nestle is simple and demonstrated with two charts. First, the chart of the group’s organic revenue growth vs the growth rating being priced in by markets against the backdrop of the share price. From 2004 to end 2011, Nestle’s organic revenue growth was consistently above the growth rate that was being priced into the shares. In other words you could buy growth at a discount, ie Cheap. After that point, the relationship inverted and markets were pricing growth at a premium to that being delivered, a feature that has become more pronounced as organic revenue growth rates erode, ie Expensive. As the Growt-rater automatically provides target price ranges (second chart) one can see that the time to buy Nestle was before the shares outperformed and the to sell it before it went down. Now how about that for a revolutionary investment strategy!