Are equity markets expensive?

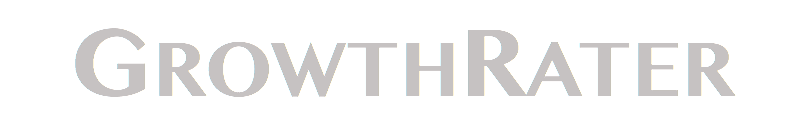

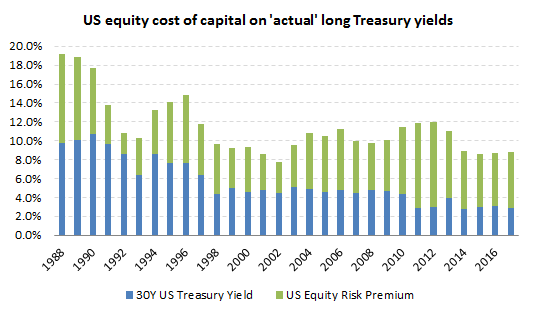

This is a regular question posed by investors and market commentators, but in many ways is also the most meaningless. This is because the relative merits of equities as an asset class owes more to the ebb and flow of liquidity to goose demand, rather than some theoretical notion of a ‘correct’ valuation that should apply to any of these. How many market shorts over the last couple of years have been squeezed into submission for believing a 20x earnings multiple is a sell signal? There is nothing magical about a 5% earnings yield. True, a rise in risk free rates may compress the relative returns for risk assets, including reductions in profitability, but how much of this rate normalisation has already been priced into equity valuations? With long Treasury yields under 3% and TIPS below 1%, the far greater issue would seem to be the level of earnings forecasting risk over the next couple of years rather than a rise in risk free rates of possibly less than +100bps. Think less about the rating therefore and more about how far the market may aim off on its earnings and FCF expectations.

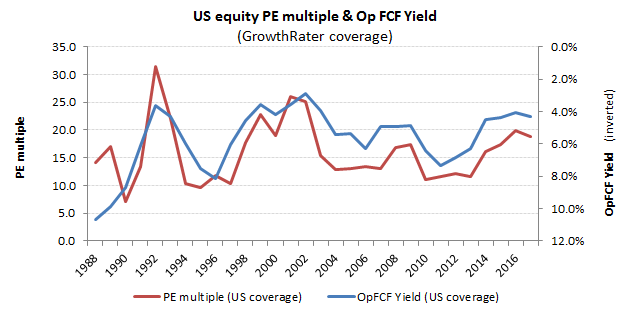

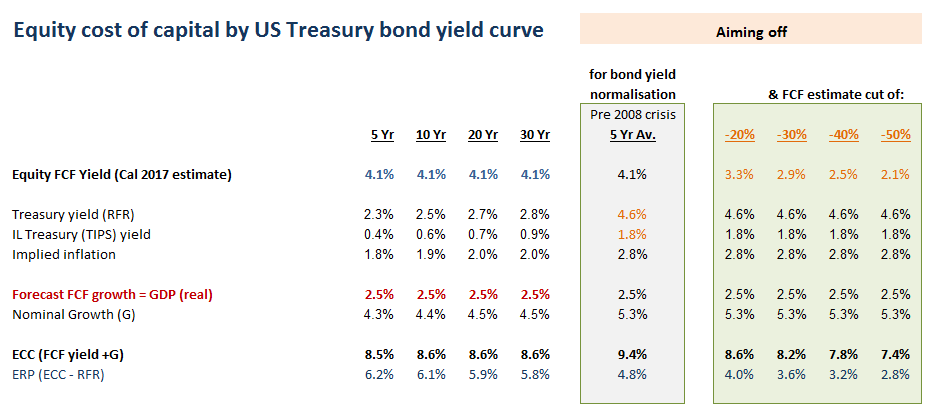

Reflecting the pattern of earnings and FCF yield, the equity cost of capital also appears near to a cyclical trough, albeit including a very different component of risk premium and risk free return.

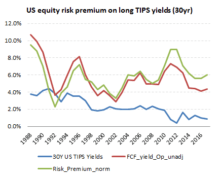

Folding in the long treasury bond yield as a proxy for the risk-free return and the gap with the long TIPS yield for the implied inflation rate and equity valuations start to look very different. First, from the perspective of the equity risk premium, equity valuations are not particularly elevated, except during the initial phase of QE, where markets were clearly aiming off to anticipate a future normalisation in rates. With the programme now in partial reverse, the big question now is how representative are current US treasury rates (including TIPS) in reflecting real market risk free and inflation expectations. Current TIP yields (of approx 0.9%) remain almost 150bps below their average levels a decade ago, although the implied inflation from the long Treasury/TIPS yields (of just under 2%) looks fairly robust in the context of a tightening monetary cycle. With up to $4t of Obama’s monetised debt to sell, it would not be unreasonable to expect the additional supply to edge up TIPS and Treasury yields over the next year, although the return to more honest financing may encourage markets not to have to aim-off to such an extent. While other central banks continue to monetise their own debt, the US stance and already higher yields (plus cash repatriation) may end up supporting enough new demand without pushing rates up that much. A modest TIP/Treasury yield uplift therefore may well be less than the extent to which markets ease off on their risk premium adjustments.

Clearly, the 100bps decline in TIPS yields from 2010 following QE was supporting to equity valuations, as was intended, but the noticeable feature here was the reluctance of markets to play the game, with market OpFCF yields rising by double that and the implied equity risk premium spiking up to over 8%. The Fed had to repeat the QE strategy several more times to persuade to bring down its risk premium on equities and even then it remained above the pre-2008 average.

A cursory glance at equity valuations reveals markets have been aiming off during the QE years. How this was constituted between the various variables may never be known, but the drop in average ECC was less than contraction in the implied inflation during this period which meant markets were either pricing against a return or a more ‘normalised’ long TIPS yield or were discounting on the earnings projections. Markets aren’t dumb and know they were being played by the central banks and politicians (as in 2008), so it is not unreasonable to assume prices would not slavishly follow the official narrative and consensus forecasts.

As the US Fed attempts to normalise rates and its balance sheet, this however raises a couple of issues. Firstly, will the return to more honest financing restore confidence in pricing risk off the long TIPS yield again and will this reduce the effective rate that markets had really been pricing into valuations? Against this however, may be an offsetting increase in forecasting risk on earnings expectations. As with early 2008, there’s not much point in assuming consensus earnings forecasts provide little more than another extrapolation of current trends, while the impact on consumption from higher rates doesn’t seem fully factored in to a number of estimates (auto?), notwithstanding the recent tax reforms. On current market rates and forecasts, the ECC comes out at approx 5.8%, or around +100bps above the average ahead of the 2008 crash. This is not to say this is either too low or too high, but merely shows the estimated return premium on equities as is. In the below table I have presented a ‘what if’ on a normalisation of bond yields back to the pre 2008 average while also folding in 4 scenarios of earnings/FCF forecast reductions should such a normalisation provoke another recession.