Ryanair – when the music stops

Many companies resemble sharks. Not just for their need to keep eating new prey to grow, but to keep growing to stay afloat. The capital intensive airlines are perhaps the most glaring example of this in action, particularly given the additional scale advantage that can be secured. The problem for investors however, is being able to identify the extent to which an aggressive expansion is covering up for low inherent returns and what might happen when this expansion slows, as ultimately always happens. At this stage the low cash conversion may be revealed as more than just the lagged effect of CapEx on depreciation, or the funding of working capital to support this growth. At this stage, investors might belatedly inquire whether the assumptions on asset lives and residual values that underpinned these low depreciation rates were over-stated, albeit by then it’ll probably be too late.

So what relevance you might say has any of this for the darling of the sector, Ryanair? Today’s announcement of its FY18 results were well received, notwithstanding cautioning on the forthcoming year’s earnings on rising fuel and staff costs. Instead, guidance for a +7% rise in capacity on flat loading in FY18 and hopes for a stabilisation of ticket prices into the second half of the year seem to be what markets are focusing on. Behind the bravado of being able to out-compete its rivals however, there are some more worrying traits within the group’s narrative, as competitors try and ape Ryanair’s cost efficiencies and practices, but also as Ryanair experiences some of their own headwinds in terms of staff cost inflation. Competitors meanwhile are consolidating and appreciate the importance of scale, albeit this means that capacity growth will continue to be driven ahead and probably faster than demand. What that does, is to potentially undermine prospects of a hardening of ticket prices to pass on rising fuel costs and therefore the assumptions of a second half pickup in revenues and margins. At some point in this battle for market share, weaker participants will have to concede, but for the moment, this is not something that can be counted on.

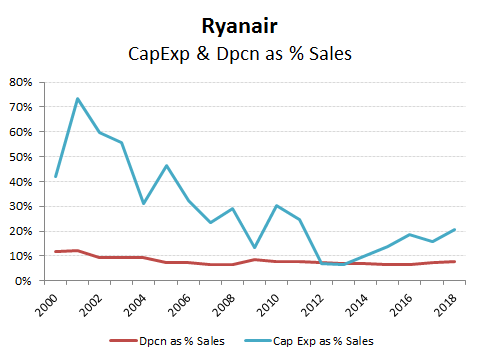

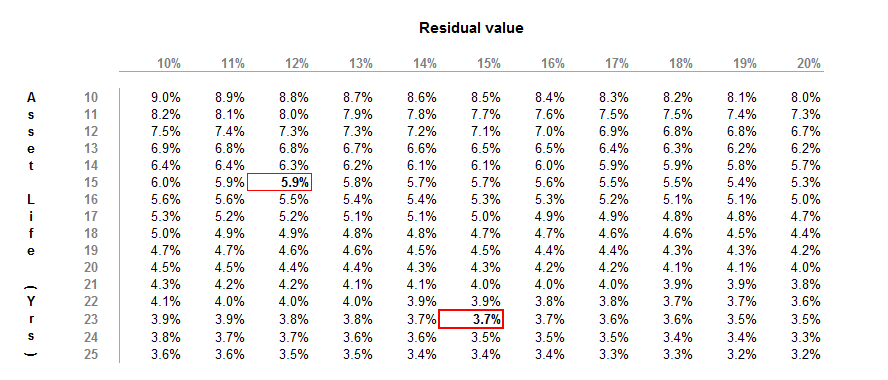

Too much investment in adding capacity means more planes being bought, which as well as depressing yields as carriers attempt to protect loadings and marginal revenues, also has implications for residual values. Traders may wish to compare earnings multiples, but investors may wish to estimate the real return management is extracting on its assets, such as a CROIC metric. Ryanair has grown organic sales rapidly over the last 5 years (at approx +8% CAGR), but it has converted only just over 50% of its net income into FCF, with the remainder funding that growth in the form of new plane acquisition and working capital. It’s policy on depreciating its plane acquisitions over 23 years and assuming a 15% residual value on these (against replacement cost equivalent at that stage) are assumptions that are not easy to test. For a mainly short-haul carrier where the aircraft are making a high frequency of take-offs and landings, this might seem a lengthy asset life to depreciate while an over-supply of capacity might also be expected to depress residual values. If so, then one may wish to either aim off and below the officially reported margins (as the below table on the implied depreciation cost by asset life and residual value shows), or assume a more modest net income to FCF conversion at whatever terminal growth assumption is being used in your selected valuation horizon.