Market crash? – depends who blinks first

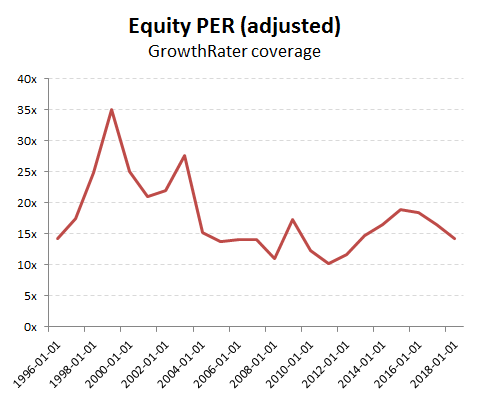

Although the GrowthRater is a relative engine to establish stock valuation and risk relative to to broader market equity returns, that doesn’t mean we aren’t keenly aware of what these are, or might become, it is just that we do not impose our view on whether this is good or bad on the investment process. A common question that we often see asked is whether the market is cheap or expensive when framed against that favourite pricing metric, the PE ratio, which is currently standing near a 10 year high. On our non-financials coverage universe, which is across 10 global sectors and markets with a combined market value of over 7tn and sales of over $6tn, provides what ought to be a reasonably representative sample, we have the ‘adjusted’ PE ratio to be currently trading at just under 19x 2016 ‘adjusted’ earnings. ‘Adjusted’, that is to exclude largely self certified ‘exceptional’ and non-trading items including amortised acquired goodwill, but including stock compensation expense which some US group’s like to exclude.

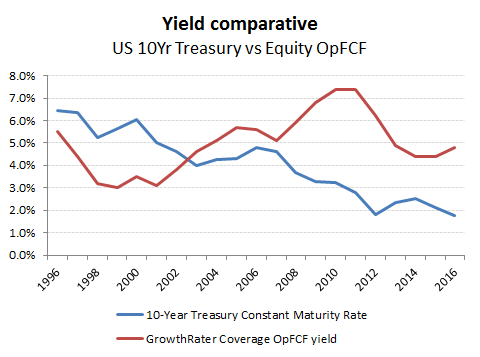

Unfortunately, whilst popular,the question is framed around an inappropriate metric. An early lesson I learnt in finance was that returns need always to be measured on a relative basis. What was an attractive yield a decade ago, may not be so compelling today if a better return from a comparable instrument is now available. Of course, in the current financial environment, the reverse would apply. What this means, is that the equity market is not cheap or expensive by virtue of whether it is currently at a medium term high against a probably flawed post interest earnings metric, but how the cash return plus the expected growth compares with a risk free proxy such as a long dated government bond. Frame the question around these and you might get a very different perspective on where equities are priced. It also gets the investors back to trying to second guess the key principal driver to valuations, the cost of capital and the distorting effects of central banks/governments interfering with what used to be taken as a proxy for a risk free return, the long dated government bond (and indexed linked). Welcome to the world of financial repression where governments (let’s be honest about who are really behind this) monetise their deficits by punishing savers and rewarding the feckless under the pretext of saving the economy and stimulating growth; which is just a euphemism for encouraging consumers to load up with ever more debt and drive investors into increasingly risky assets and for companies to buy-back their shares rather than invest in improving capacity. The implication for equity investors, is that notwithstanding the fall in the running yield (OpFCF) on equities since 2011, the relative return against the risk free return is approaching 3ppts, which is almost three times the premium equities were standing on in the half decade ahead of the 2008 financial crisis. Perhaps equities are not so expensive after all!

The return premium on equities however, is more than just the running yield gap between the normalised operating free cash flow yield on equities versus the redemption yield on long gilts or treasuries, as equities cash flows are hopefully growing in real terms. Despite a significant, but measurable level of cyclical volatility, the longer term real organic growth in equity Op FCF ought to match the broader economy, which with global population growth of over +1.1% pa has been sustaining a relatively steady longer term real rate of growth around +2-3% CAGR. Including the prospective inflation expectation built into the long bond/gilt market (long fixed less long indexed linked yields) of approaching 3% pa and one should be looking to add a nominal trend growth of approx +5% to the current 4.5-5.0% OpFCF yield on equities. While deflationary junkies would argue for a lower inflationary assumption, this is not what is actually being implied by bond markets and might be a case of recency bias and falling for central bank spin.

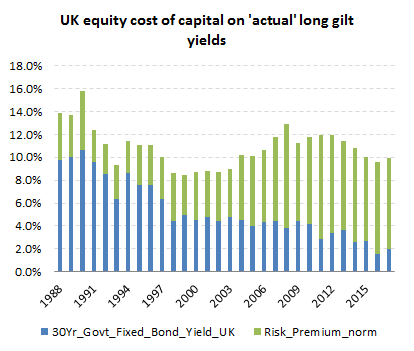

Taking the current market long bond yields and equity earnings expectations and the forward ECC may have been declining consecutively now for about four years, but is still slightly ahead of the absolute rate over most of the decade ahead of the 2008 financial crisis. Exclude the long bond yield and the implied equity risk premium is at an all time high of around 8%. If one takes recency bias to extremes and assume both equity earnings expectations and current market bond yields are sustainable, then this would not seem to suggest an imminent demise of equity prices, at least on valuation grounds.

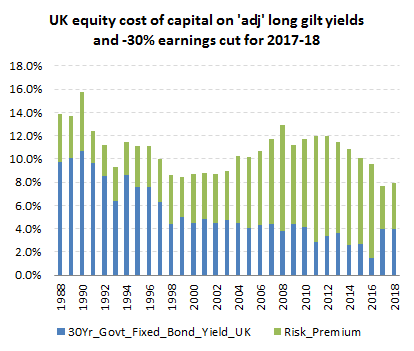

This of course highlights the pernicious effect of financial repression in distorting the pricing of risk and an increasing misallocation of capital. For what was originally sold as a temporary liquidity fix has morphed into a funding support for structural deficits from which governments and central banks now seem incapable, or at least unwilling, to ween themselves from. This is a world where over $13 tn of government bonds are priced on a negative yield, notwithstanding continued increases in deficit spending which will only deteriorate further as rising age demographics threaten to double the ratio of retirees vs working age groups across developed markets over the next 10-15 years. The traditional solution by politicians has been to accelerate immigration to help offset this trend, although recent attempts at this in both Europe and the US appear to have provoked a sizeable popular back-lash, which in Europe at least, threatens the very existence of the EU in its current form, and as a consequence, also the Euro and ECB. Take away the ECB with its support for Southern European deficit funding and sub-prime auto loans and equity markets could face a double whammy of a reset in bond yields (and risk free return assumptions) at the same time as consumption and equities earnings forecasts are hammered – a very nasty combination. Markets understand this will end badly and that the longer the proverbial can is kicked down the road, the more difficult it will be to engineer a soft landing, but the continued pursuit of the strategy by Japan, the ECB and PBoC suggests that ultimately it will be left to currency markets to restore fiscal discipline to governments. In the meantime, in between chasing the carry trade of cheap debt to buy a higher equity running yield, investors might also wish to keep an eye on how the ECC and risk premium could look like an a slightly less favourable bond yield and earnings outlook. In the below chart I have included a normalisation of long bond yields back up to 4% while also including a -30% cut in market earnings spread over 2017 and 2018 by way of example.

Markets aren’t dumb and know there will be a probably painful reset. Investors are being starved of returns however, and like the animal at the water-hole, need to drink and will pursue the carry-trade until the last moment and beyond, hoping central banks defer the inevitable because all are playing the game. The problem though may be that this places enormous trust in the US that it won’t ask for its ball back. The market’s assumption seems to be that the Fed is caught in an easing cycle that it can’t escape and that beyond the endless warnings of an imminent rate increase it will keep rates low and continue to pump liquidity into markets and thereby financial repression and asset prices. With every weak data point, such as auto sales or non-farm payrolls or external event such as Brexit or falling oil prices, markets see take this as further evidence that the game has further to run, particularly as NIRP policies in Europe and Japan take pressure off the US dollar.

To assume that the US is so desperate to support global growth that it is trapped into a perpetual low rate strategy however, may be to fundamentally misunderstand its key priority; that of the US dollar and its unrivalled position as global reserve currency – but more on this another time.