US debt ceiling and the point of no return

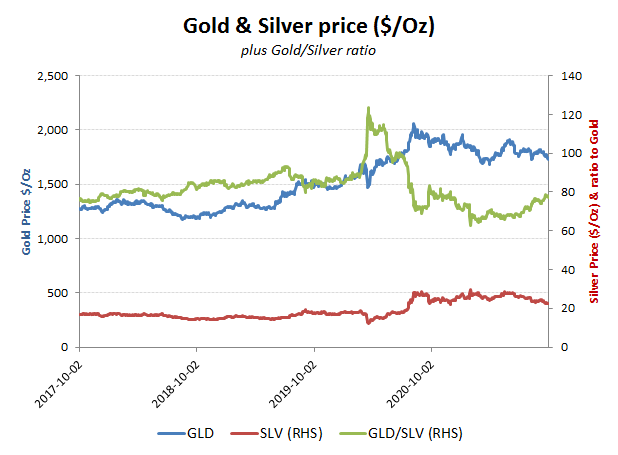

What is the drifting gold price trying to tell us, because rising inflation and reckless government fiscal policies suggests impending currency debasement? Is this just another case of cognitive dissonance, that has accompanied COVID-19(84), or perhaps a temporary phenomena such as a big holder being forced to sell gold to raise USD to cover some rising oil bills and some souring property loan books.

Precious metals are off their peaks

On the other hand of course it might also reflect a growing awareness that a failing Biden regime is looking less able to push through its $3.5 trillion budget and if it can’t even extend the debt ceiling to avoid the impending defaults by mid October (Yellen last predicted the 18th October, but with Govt funding now agreed in the Senate up to 3 Dec, this year), then they can’t even print their way out of the hole they have dug for themselves. This of course suggests markets are still giving the US and dollar the benefit of the doubt that it hasn’t gone beyond the point of no return and that the transition to a return to market pricing of capital and interest rates can be achieved without a currency collapse and loss of reserve currency status.

Debt ceiling extension: The usual Kabuki, or is it different this time?

Could it be different this time? The US Congress has been about to breach its debt ceiling limit 78 times already since 1960 and each time, amidst the usual warnings of financial catastrophe, the nation’s credit limit has been dutifully extended. The assumption by markets therefore has been that after the usual political posturing and horse-trading that there will again be a last minute deal to extend the government’s borrowing limit, which in turn will leverage through the proposed budget.

There is much that is different in today’s politically charged environment however. Election audits will only proliferate following the coordinated fraud uncovered in Arizona, which will also only increase the proportion of voters (>40% already) who question the last election integrity and therefore legitimacy of not just of the President, but also many of those returned at that point to Congress. Add into that mix the emerging indictments from the Durham special counsel, Biden’s failure to manage the Afghanistan withdrawal, his increasingly authoritarian rule by executive order and medical tyranny and this is a society that is on the edge of serious civil unrest. In this context it is therefore quite plausible to envisage a polarised Senate blocking the extension of the debt ceiling and to drive a failing administration in financial default. This time therefore the debt ceiling extension may well provide the first major catalyst in the political push-back, while also representing a bellwether on whether the US dollar is a hopeless case, or if honest money can ever be restored.

On Wednesday (29 Sept) Pelosi’s Debt Ceiling Suspension Blll (to 22 December 2022) squeezed through the House of Representatives with a 219-212 majority, but without support from more fiscally conservative Democrats in the Senate, such as Senator Joe Manchin, this looks to be dead on arrival at the upper house. Congress has a September 30 deadline to renew expiring government spending authority for the 2022 fiscal year that begins October 1. Failure to do so would result in a government shutdown. Today’s 30 Sept deadline seems to have got McConnell to blink first and agree a temporary extension in funding the Govt until 3 December this year, although I not aware of any increase in the overall debt ceiling being included in this.

It is important to note that the statutory debt limit applies to almost all federal debt. The limit applies to federal debt held by the public (that is, debt held outside the federal government itself) and to federal debt held by the government’s own accounts. Federal trust funds, such as Social Security, Medicare, Transportation, and Civil Service Retirement accounts, hold most of this internally held debt. As of March 24, 2021, total federal debt outstanding was just under $28 trillion. Intergovernmental debt—mainly held in various federal trust funds—totalled slightly more than $6 trillion. Debt held by the public—which includes Federal Reserve holding of Treasury debt purchased on secondary markets—was slightly under $22 trillion.

The monetised debt on the Federal Reserve is included in its balance sheet as an asset and therefore is also included in the overall government debt calculation, which means:

1. The Fed can’t use its Magic Money Tree (MMT) to debase its way out of the crisis

2. No money printing means no QE, which means the artificial cap on interest rates and bond yields is removed. – Ouch!

Okay, realists amongst the readers here will appreciate that an administration that has flagrantly trampled on the constitution and its citizens personal liberties (including the 1st Amendment and treaty obligations such as the Nuremberg Code/Helsinki Accord), is not going to concern itself on the niceties of what is legal and will conjure up some BS to try and print its way out of trouble, while brow-beating an already intimidated judiciary to look the other way. This however, will merely compound the crisis of confidence in currency markets for the US dollar and where ultimately real interest rates will be set.

The prospect of a normalisation of interest rates

After a decade of central bank manipulation of interest rates through disguised money printing and industrial offshoring is coming to an end. The money printing being used to buy back the bonds issued by the government to pay for the deficit spending while depressing yields from the artificial demand. The offshoring to depress reported inflation and thereby support the narrative that this wasn’t inflationary (which of course it was, but for asset pricing and not disposable incomes). For a number of reasons, this cycle has been breaking down and now with return to what ominously looks like a 1970’s style stagflation, the US is faced with its moment of truth; go full Wiemar, or accept the MMT party has come to an end and restore some fiscal and monetary discipline. The former will entail a currency crisis and the end of the US dollar reserve status and everything associated with that, while the latter will not be without some pain either, as interest rates normalise and savings ratios are rebuilt at the expense of current consumption.

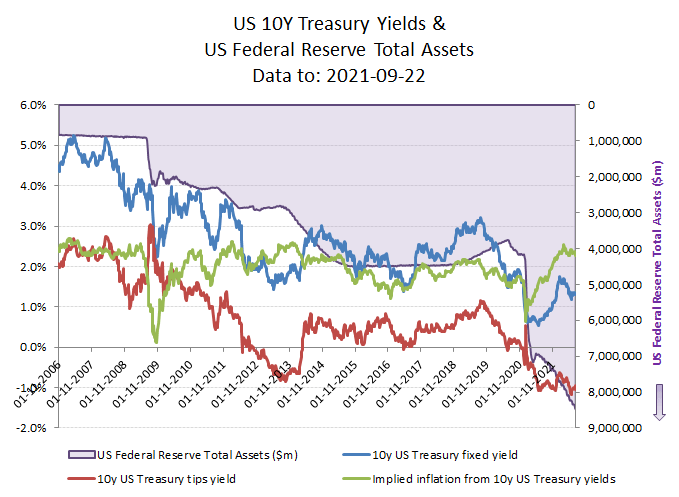

In the below chart I have attempted to show the relationship between this monetary sleight of hand by the Federal Reserve following the 2008 financial crisis to disguise its deficit monetisation via bond purchases, also known as Quantitative Easing (QE). This monetary laxative naturally came with its own TLA (three letter acronym) in the form of the MMT; known by its supporters as ‘Modern Monetary Theory’, but in reality more like a ‘Magic Money Tree’ hypothosis. The key was to depress nominal inflation (and disposable incomes) by outsourcing manufacturing to China and artificially reduce interest rates by goosing demand for new bond issuance by creating enough new credit to buy in the new debt (effectively monetising it). What initially was presented as an emergency in 2008 and therefore a temporary measure to restore market liquidity inevitably became a permanent fixture to fund the now endless structural deficit. The deceit was of course that these monetised debt purchases, which ended up on the Federal Reserve’s books as an asset, would ever get sold back into the markets and were yet another dishonest manipulation and abuse of being in control of the World’s reserve fiat currency; albeit perhaps not for long now!

The relationship between the ability to buy in unlimited amounts of ones own fiat currency and market interest rates on those debt instruments is therefore fairly self-evident. Create new demand relative to the supply and the Treasury Bond price will rise, with the corresponding fall in implied yield and interest rate. In the below chart I have included the Federal Reserve Assets in reverse order to compare the increase in this with the comparable reductions in interest rates on the 10 year Treasury bonds (both fixed and TIPS), along with the implied inflation rate from these. The key conclusions from this includes:

- The direct relationship between rising Assets and lower yields since the introduction of this policy since 2008

- An approx 6 month lag at times to reflect expectation management by the Fed of intended expansion (QE) programmes and also potential tightenings (QT)

- Normalised real yields, prior to QE were approx 2.0-2.5%

- Without the exceptional monetary expansion currently in place, a normalisation in rates on a +2.5% implied inflation rate would suggest a rise in 10 year Treasury yields back to 4.5-5.0% again.!

A decade of Central Bank manipulation of interest rates may be coming to an end!

It is questionable whether the US spending spree has already taken it beyond the point of no return

When Government debt is already almost +20% greater than GDP and has been funded by what has been an artificially suppressed interest rate assumption, this raises some fairly glaring challenges on how to return to the normal market pricing of capital. Over the past decade, the Fed has been able to raise 10 year debt at around 2-3% on average (currently at approx 1.5%), with shorter term borrowings at nearer 1%. As mentioned above, should the debt monetisation tap get turned off, then the cost of raising new debt as previous tranches mature and require re-financing could rise significantly and perhaps to nearer 4-5% on a proforma basis that would represent an increase in funding costs of +2-3ppts. On $28 trillion of debt, this would equate to an additional +$560-580bn pa of funding costs (equivalent to a structural cut in GDP of approx -2.3-2.4ppts pa). While the full impact of this would be spread over perhaps 7 years, as previous tranches of debt matures and requires refinancing to the higher rates, there would be other factors that would tend to negate some of this. These would include the rate shock to the broader economy, including mortgage rates, where these rate increases would feed through more rapidly to reduced economic activity and consumption. These in turn would cascade down thru to reduced tax receipts and therefore even greater pressure on budget deficits, along with inflationary pressures, potentially triggering a spiral in debt issuance demands. Welcome to the return to stagflation and the penalty for governments treating public finances like a ponzi scheme!