How many jobs added in July??

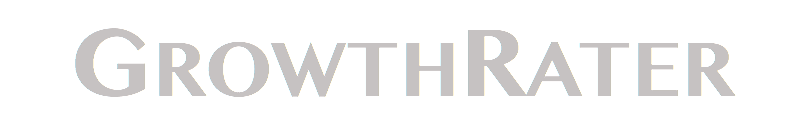

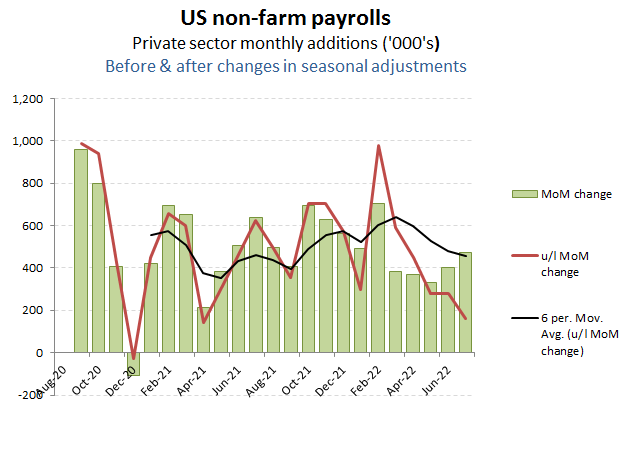

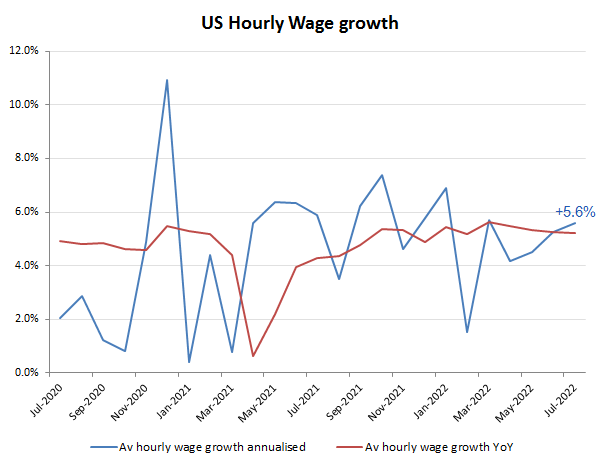

Perhaps Biden was correct and this is not a recession, as the US reports another increase in monthly private sector jobs in July. This time from June’s reported +404k net adds to almost half a million (+471k) in July, with annualised hourly wages meanwhile increasing by +5.6%. But hang on, if one strips out the changes in seasonal adjustments and the additional +309k net jobs parachuted into the reported figures by the BLS, then the real monthly job growth figure tumbles from +278k in June to only +162k for July. No surprise to see the Government fiddle its statistics, but is the narrative being constructed to help encourage the obviously reluctant Fed to ‘walk the walk’ on its tightening commitments?

“There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and [government] statistics” so said some long deceased politician. Well, little seems to have changed, except our better access to the data has perhaps made some of the official sleights of hand more obvious to us mushrooms. Changing the seasonal adjustments to what are already largely guesstimates by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) is an old favourite and it seems particularly well used over the past few months to reverse what would have been a steep decline in US private sector monthly net job growth into two consecutive months of increases. Now where have we heard this one before?

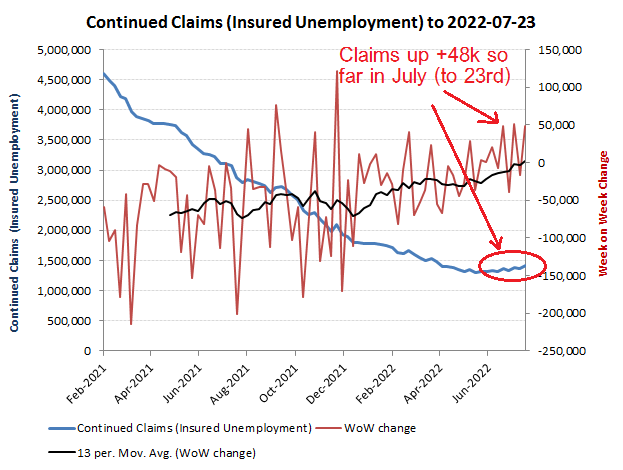

A useful check for the BLS employment survey data statistics can be the weekly claims for insured unemployment, which looks at the issue from the other end of the pipe, so to speak. While eligibility can distort the data, it nevertheless can flag a possible problem when there is a significant inconsistency. So for example, when the BLS is estimating a robust upward trend in monthly jobs growth, but more people are making claims for unemployment, as is the case at present with July’s continued claims up to the 23rd increasing by 48k. So more people are getting jobs, but more people are also claiming for unemployment. One statistic however is derived from an extrapolated survey, while the other reflects actual claims for hard cash. I know which metric I would use as being more reliable!

Although less pertinent if job growth is weaker than officially claimed, the reported increases in estimated average wages when combined with the official BLS data might well be used to construct or support a narrative of an overheating labour market. Such a narrative might also be seen as supportive of tightening monetary policy into a recession, that’s not a recession (according to one’s personal definition, it seems!).